A comprehensive, guide to Fla. Stat. §§ 455.225 and 455.2255 (and how Chapter 120 fits in)

This post is for general information, not legal advice. Every board (CILB, ECLB, FREC, etc.) layers its own rules and penalty guidelines on top of these baseline statutes, so the details can shift depending on the profession and the charge.

Who this applies to (and why it matters)

Florida’s Department of Business and Professional Regulation (“DBPR”) regulates many licensed professions. When DBPR (or a board under DBPR) investigates and disciplines a licensee, the core framework is in Fla. Stat. § 455.225.

Separately, Fla. Stat. § 455.2255 governs when certain discipline can later be reclassified as “inactive” (and sometimes cleared) so it is no longer treated as part of the licensee’s disciplinary record—including the ability, in specific circumstances, to lawfully deny the incident as discipline.

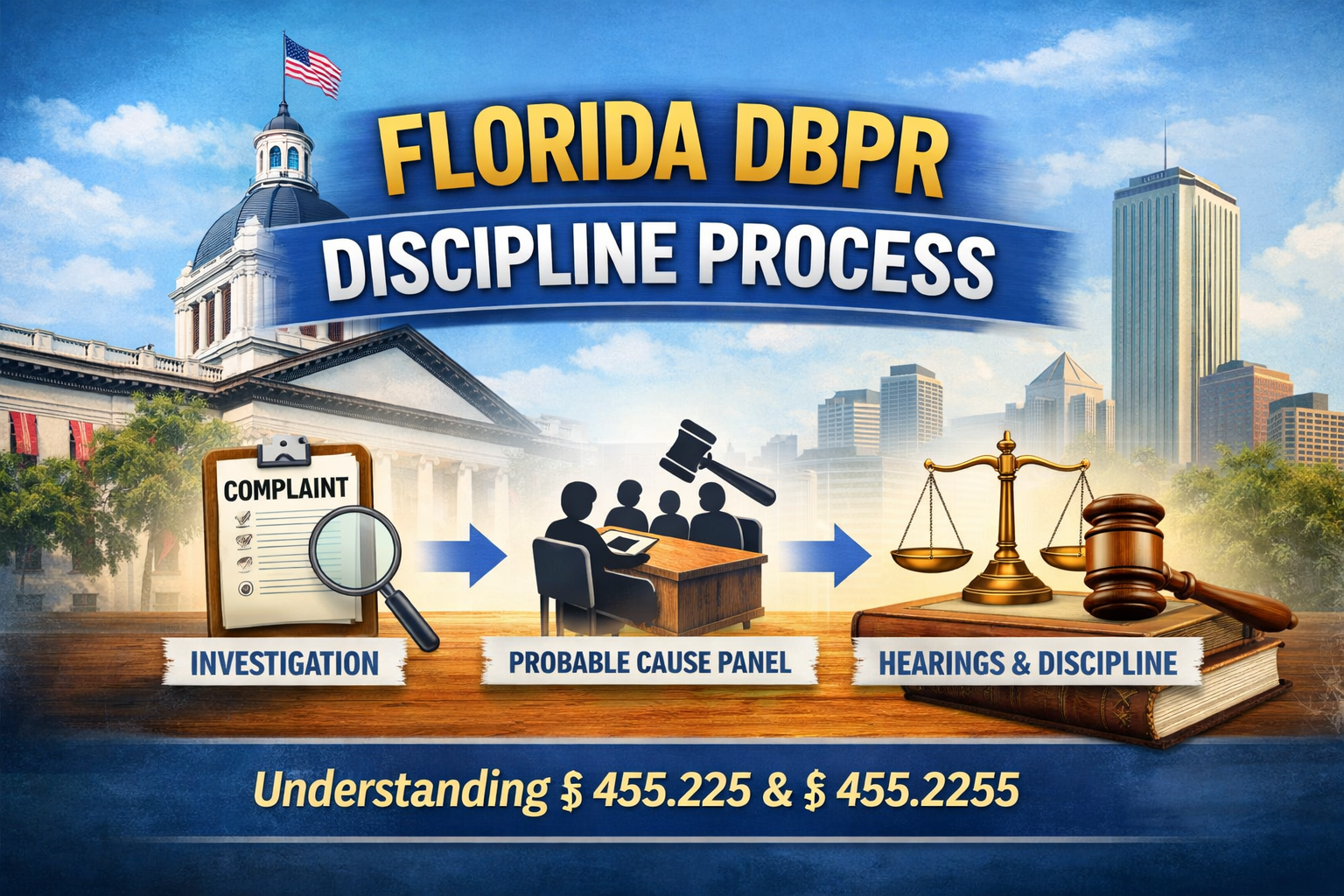

The big picture flow (process map)

Complaint → Legal sufficiency → Investigation → Probable Cause (PC) Panel

→ No PC / Letter of Guidance / PC Found

→ If PC Found: Administrative Complaint → Chapter 120 hearing track (informal or DOAH)

→ Final Order (discipline imposed or case dismissed)

→ (Later, in some cases) § 455.2255 reclassification/clearing

PART 1 — The disciplinary pipeline under § 455.225

1) The complaint stage: “legal sufficiency” is the first gate

DBPR does not (in theory) fully investigate every grievance. The statute focuses DBPR’s resources on complaints that are legally sufficient—meaning the complaint alleges facts that, if true, would violate the professional practice act, Chapter 455, or an applicable rule.

Key points:

- DBPR must investigate written, signed legally sufficient complaints (and can open certain investigations on its own information).

- DBPR can require additional information from the complainant to determine legal sufficiency.

- Withdrawal by the complainant does not necessarily stop the process.

Practical takeaway: The earliest “win” is often showing DBPR that the allegations—taken as true—do not actually describe a statutory/rule violation (or that DBPR lacks jurisdiction).

2) Notice to the subject + the 20-day response window

Once an investigation is opened, DBPR generally provides the subject (or counsel) the initiating complaint/document and gives a statutory opportunity to respond.

- The subject may submit a written response within 20 days after service, and the response must be considered by the Probable Cause Panel.

- DBPR can delay notice in limited circumstances (for example, where notice would be detrimental to the investigation, or the conduct is criminal).

Practice tip: Treat the 20-day response like a mini-brief. It may be your best chance to prevent a probable cause finding before the case becomes public.

3) Investigation: fact gathering + DBPR’s investigative report

If the complaint clears legal sufficiency, DBPR investigates and prepares an investigative report and recommendation for the Probable Cause Panel.

Important features:

- DBPR can dismiss a case (or part of a case) if there is insufficient evidence to prosecute.

- The Probable Cause Panel can, in certain circumstances, push forward even when DBPR wants to dismiss (the statute contemplates panel authority to pursue/prosecute through retained counsel).

4) “Minor violation” lane: notice of noncompliance (not full discipline)

Section 455.225 contains a softer lane for initial, truly minor issues.

- For an initial “minor violation” (as defined by the statute’s standards), DBPR may issue a Notice of Noncompliance rather than initiating full discipline.

- If not corrected (commonly within 15 days), DBPR may proceed with “regular disciplinary proceedings.”

Practice tip: If the facts fit, pushing a matter into “minor violation” treatment can prevent public/prosecuted discipline—and it can matter later for § 455.2255 relief.

5) Probable Cause Panel: confidentiality, composition, and deadlines

The Probable Cause Panel is the statutory gatekeeper—deciding whether the state will formally charge the licensee.

Panel composition (not just a formality):

- Must include a present board member and a former or present professional board member (former must hold an active, valid license for that profession).

- Proceedings are exempt from the Sunshine Law until 10 days after probable cause is found (or the subject waives confidentiality).

Timing mechanics:

- Panel can request additional investigative information within statutory time limits.

- The statute sets deadlines for probable cause determinations and a backstop where DBPR may make the determination if the panel does not.

Possible outcomes at PC stage:

- No probable cause (case ends at this stage),

- Letter of guidance (non-disciplinary guidance/warning), or

- Probable cause found → directive to file a formal administrative complaint.

6) Once probable cause is found: the case goes “formal”

A probable cause finding authorizes (and typically directs) DBPR to file a formal administrative complaint and prosecute under Chapter 120 (Florida’s Administrative Procedure Act).

At this point, the matter becomes more like litigation: pleadings, evidence, witnesses, and a record that supports a final order.

6.5) The Election of Rights (EOR) form — the pivot point after the Administrative Complaint

After DBPR files and serves an Administrative Complaint, the Respondent is typically served with an Election of Rights (EOR) form (or a “Notice of Rights”) that requires the Respondent to choose the hearing track under Florida’s Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”). This election is the procedural “fork in the road” that determines whether the case proceeds as a formal DOAH hearing (trial-like) or an informal hearing (mitigation/penalty-focused).

Statutory authority. The EOR process is grounded in Chapter 120, not § 455.225. The notice-and-election framework comes from § 120.569 (Decisions affecting substantial interests), which requires the agency’s notice to explain the available hearing rights and deadlines, and § 120.57, which sets the two main hearing procedures:

- § 120.57(1): formal hearing at DOAH when there are disputed issues of material fact;

- § 120.57(2): informal hearing when there are no disputed issues of material fact and the issues are typically mitigation, public protection, and the appropriate discipline.

The deadline (“point of entry”). The response deadline is usually described as the “point of entry” into the administrative proceeding. Many DBPR notices reference the uniform administrative rule that generally uses a 21-day window from receipt of notice (unless a more specific statute/rule applies). The controlling deadline is the one stated in the document you were served, so it must be calendared immediately.

Why this matters. The election can significantly affect your options:

- If you elect an informal hearing, you are generally proceeding on undisputed facts (or stipulated facts), meaning the dispute typically focuses on penalty and mitigation, not whether the alleged conduct occurred.

- If you elect a formal DOAH hearing, you are asserting that material facts are disputed, which triggers an evidentiary hearing before an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ).

- If you miss the deadline or fail to properly request a hearing, you risk waiving hearing rights and allowing DBPR to proceed toward a default and final order.

Practical rule of thumb: If you truly dispute the core facts alleged in the Administrative Complaint, elect DOAH/FORMAL HEARING. If the facts are essentially undisputed and the main issue is the appropriate discipline, an informal hearing may be the correct posture. If unsure, Err on the side of requesting the Formal Hearing so that option is not deemed waived.

7) Critical clarification: DBPR can still decline to prosecute (“improvidently found” PC)

This is a point many licensees miss:

Even if the Probable Cause Panel finds probable cause, DBPR may decide the finding was “improvidently found”—meaning DBPR believes it was mistaken or not supportable—and DBPR may decline to prosecute.

Then:

- DBPR must refer the matter to the board, and

- the board may still choose to prosecute anyway (often through retained counsel), by filing the administrative complaint and pursuing the Chapter 120 case.

Plain-English takeaway: Probable cause does not guarantee DBPR will prosecute—and DBPR’s refusal does not necessarily end the case if the board elects to proceed.

8) How Chapter 120 hearings work (informal vs DOAH formal)

Once an administrative complaint is filed, the hearing track depends largely on whether there are disputed issues of material fact.

A) Formal hearing at DOAH (disputed facts)

- If material facts are disputed, the case proceeds to a formal hearing before an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) at DOAH under § 120.57(1).

- The ALJ issues a Recommended Order, and the agency/board issues a Final Order based on that record (with legal standards governing deviations).

B) Informal hearing (no disputed facts; mitigation/penalty focus)

If the licensee does not dispute material facts, the case may proceed as an informal hearing under § 120.57(2) (often focused on explanation/mitigation and appropriate discipline).

Important: If an informal hearing starts and disputed facts emerge, the matter is typically pushed to the formal DOAH track to resolve the factual disputes on a proper evidentiary record. (This is consistent with how § 455.225 ties contested fact issues to formal hearing procedures.)

9) Final order: who decides, and why PC panel members usually don’t

Ultimately, the board (or DBPR where there is no board) issues the Final Order, which is final agency action for purposes of appeal.

A common safeguard: members who served on the Probable Cause Panel are generally not the ones deciding the final discipline (to avoid mixing the gatekeeper role with adjudication).

10) Emergency lane: summary suspension / restriction under § 120.60(6)

Separate from the normal pipeline, DBPR can pursue summary suspension, restriction, or limitation when it finds an immediate danger to public health, safety, or welfare.

- The statute requires the agency to state specific facts and reasons supporting immediate danger and procedural fairness.

- Summary action can happen fast, but the agency must also promptly proceed with the underlying administrative process to determine whether the restriction should become permanent.

Practice tip: These cases are won or lost on (1) the immediacy/danger findings and (2) building a record quickly for review.

PART 2 — Keeping (or clearing) discipline off your “record”: § 455.2255

Section 455.2255 is about what happens after discipline—especially older, lower-level discipline.

1) Petition to reclassify a “minor violation” as inactive (and then deny it)

A licensee may petition DBPR to review a disciplinary incident and determine whether it meets the minor violationstandard referenced in § 455.225(3).

If it qualifies and:

- 2 years have passed since the final order imposing discipline, and

- the licensee has not been disciplined for a subsequent minor violation of the same nature,

then DBPR shall reclassify that violation as inactive.

What “inactive” means (this is the money line):

- Once reclassified, it is no longer considered part of the licensee’s disciplinary record, and

- the licensee may lawfully deny or fail to acknowledge the incident as disciplinary action.

2) Classification schedules and “clearing” beyond minor violations

Section 455.2255 also contemplates broader classification by severity over time—where violations may be made inactive and, in some circumstances, later cleared from the disciplinary record.

3) Applies to all DBPR licensees (persons and businesses)

The statute applies broadly to disciplinary records of all persons or businesses licensed by DBPR, notwithstanding § 455.017.

Practical takeaway: If the case ends in discipline, strategy doesn’t stop at the final order. A “minor violation” outcome can create a path to future reclassification and lawful denial under § 455.2255.

What to do when you (or your business) receives a DBPR complaint

Here’s a practical checklist that aligns with the statutory structure:

Immediately (Day 1–7)

- Identify the board and statute/rule at issue (not all “bad facts” are actually chargeable violations).

- Preserve and organize documents, emails/texts, job files, permits, contracts, and proof of compliance.

- Calendar the 20-day response window and treat it as deadline-driven.

Before your 20-day response is filed

- Build the response around the PC panel’s decision lens:

- “Even if everything alleged is true, this is not a violation,” and/or

- “Key facts are missing/wrong; here is the documentary proof,” and/or

- “This is a minor/correctable issue appropriate for noncompliance treatment.”

Once probable cause is on the table

- Decide early whether you will:

- contest material facts (DOAH formal hearing track), or

- accept facts and argue mitigation/penalty (informal hearing posture).

If a final order enters discipline

- Evaluate whether the incident could qualify later for § 455.2255 reclassification, and calendar the 2-year mark from final order if applicable.

Common FAQ (plain English)

“Is the complaint public right away?”

Typically no. The investigative phase is generally confidential until the statute’s release point (including the “10 days after probable cause” rule for panel proceedings), unless confidentiality is waived.

“What is probable cause in this context?”

It’s the statutory threshold decision that there is a sufficient basis to proceed with formal charges—not a final finding of guilt.

“If probable cause is found, am I automatically prosecuted?”

Not necessarily. DBPR may decline to prosecute if it believes probable cause was improvidently found, and then the board may decide whether to prosecute anyway.

“What’s the difference between an emergency suspension and a normal case?”

A summary suspension/restriction under § 120.60(6) is an emergency tool based on “immediate danger.” It moves fast and is reviewed through a different posture than ordinary discipline.

“Can I ever get an old disciplinary action ‘off my record’?”

In some cases, yes. If it qualifies as a “minor violation” and the statutory conditions are met, § 455.2255 provides a path to reclassification as inactive, which allows lawful denial/failure to acknowledge the incident as discipline.

Closing: why early positioning matters

In DBPR cases, the strongest leverage often comes before probable cause—when the matter is still confidential and the PC panel is deciding whether formal prosecution is warranted. Once an administrative complaint is filed, the process becomes more litigation-driven under Chapter 120, and outcomes can carry long-lasting licensing and business consequences.

If you’re a Florida licensee or business facing a DBPR complaint, a disciplined response strategy—framed to the statutory gates above—can materially change whether the case is dismissed, diverted into a minor-violation lane, resolved by consent, or litigated at DOAH.